|

Photo Galleries:

FINE ART

BACKDROPS

BIKE ART

GALLERY 800

GLENDALE HARLEY

ILLUSTRATIONS

LIFE OF DENIS

LOGO / SIGN

LOVE RIDE

MURALS

SKULL ART

VEHICLE

Home Page

About The Host

Affaire In The Garden

Denis Olsen - Love Ride Article

Gallery 800

Gallery 800 Invitation

Gallery 800 Online

Master of Air-On, Wear-On Art

Meet Denis Olsen

Recent Work

Links

5108 Lankershim Blvd

North Hollywood, CA 91601

United States

Tel: 818-763-8052

artunites@att.net

artunites@att.net

gallery800@gmail.com

|

|

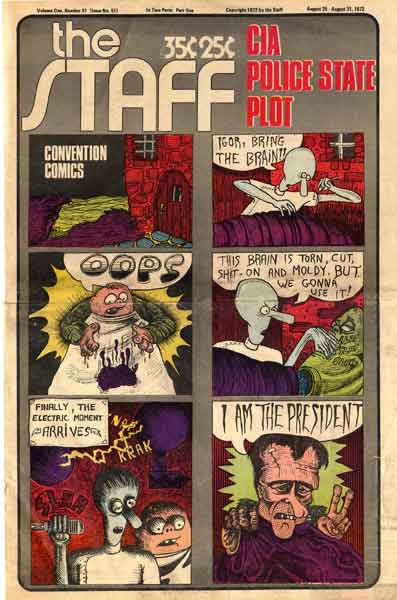

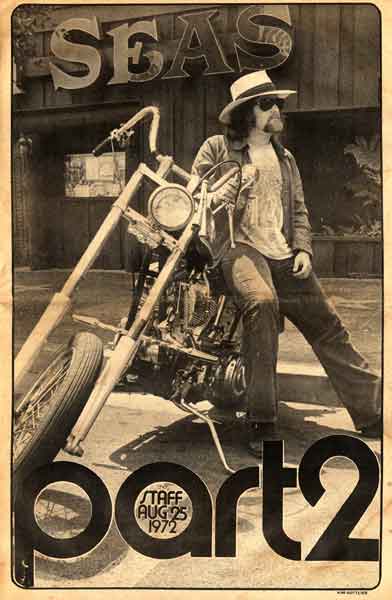

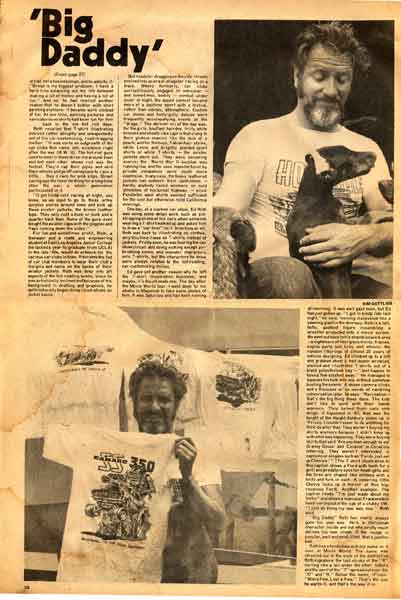

Master of Air-On, Wear-On Artfrom The L A Free press Taken from August 25-31, 1975 issue of The Staff, Vol. One, No. 51 (Issue No. 51)

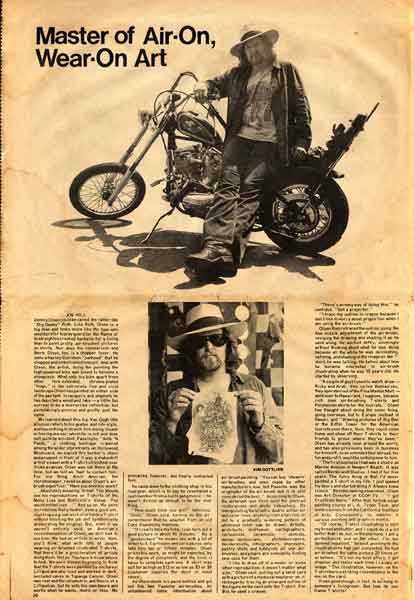

Master of Air-On, Wear-On Art

by Joe Hill and Kim Gottlieb

Denis Olsen could be called the latter-day "Big Daddy" Roth. Like Roth, Olsen is a big man and looks more like the type who would prefer to play guard for the Rams or to straighten crooked barbells for a living than to paint pretty, air brushed pictures on shirts. Nor does the comparison end there. Olsen, too, is a chopper lover. He owns a Harley-Davidson "pan-head" that he chopped and embellished himself. And with Olsen the artist doing the painting, the high-powered bike was bound to become a showpiece. What sets his bike apart from other fork-extended, chrome-plated "hogs," is the extremely fine and vivid landscape Olsen has painted on either side of the gas tank. In lacquers and enamels he has depicted a woodland lake - a little too surreal to be a mirror-like reflection, but painstakingly precise and pretty just the same.

We learned about this hip Van Gogh (the allusion refers to his goatee and life-style, and has nothing to do with him being insane or having one ear, which he is not and does not) quite by accident. Passing by "Ants 'N Pants," a clothing boutique crannied among the wider storefronts on Hollywood Boulevard, we espied this barber's chair and propped in front of it was a makeshift artist's easel with a T-shirt stretched over it like a canvas. Olsen was not there at the time, but we felt we "had" to contact him. For one thing, Amir Amirian, the store manager, raved so about Olsen's airbrush expertise: "Have you seen his work? ... Absolutely amazing. Great! You should see his reproductions on T-shirts of the Mona Lisa and Botticelli's Venus. You would not believe... And so on. We were incredulous that a dauber, even a good one, could copy a great work of art onto a T-shirt without botching the job and symbolically desecrating the original. But, even if we weren't entirely sold on Amiriam's recommendation of Olsen, we still had to see him. We had an article to write. Now, you'd think, what with lots of people wearing airbrushed illustrated T-shirts, that there'd be a proliferation of artists doing them. Not so. You have to know where to look. We were almost beginning to think that the t-shirts were painted by nocturnal liliputians who lived and worked in dark, secluded caves in Topanga Canyon. Olsen was real and the volumetric antithesis of a Lilliputian, but he sets his own hours and works when he wants, more or less. We prevailed, however, and finally contacted him.

He came down to the clothing shop in his road gear , which is to say he resembled a cast member from a cycle gang movie. He wasn't dirtied up enough to be the real thing.

"How much time you got?" Infinities. "Good, " Olsen said, turning on the air compressor that he adapted from an old Coke dispensing machine.

"If I really take my time, I can turn out a good picture in about 45 minutes." By a good picture he means one with a lot of detail to it. Cartoons and caricatures only take him ten or fifteen minutes. Olsen prices his work, as might be expected, by the degree of complexity and the time it takes to complete each one. A shirt may sell for as high as $12 or as low as $3 or $4 (customer supplies the shirt in most cases.)

As Olsen shook his paint bottles and got out his two Paasche air brushes, he volunteered some information about air-brush painting. "You can buy 'cheapie' air brushes and ones made by other manufacturers now, but Paasche was the originator of the air brush and it is still considered the best." According to Olsen, the airbrush was first used for portrait restorations and photo retouching. By manipulating the brush's double action air and color lines, anything from a airline or dot to a gradually widening pattern of atomized color can be drawn: Artist, architects, draftsmen, cartographers, cartoonists, ceramist, dentists, dental technicians, photo-developers, taxidermists, lithographers, engravers, pastry chefs and hobbyists all use airbrushes, and people are constantly finding new uses for them.

"I like to draw off of a model or some other reproduction. It doesn't matter what size," Olsen said, pulling out a tarot card with a picture of a medieval wayfarer on it. He began by tracing an enlarged outline of the figure on the card onto the T-shirt. For this he used a crayon.

"There's an easy way of doing this," he confided. "Get a projector."

"I trace my outline in crayon because I don't like to worry about proportion when I am using the airbrush.

Olsen then retraced the outline using the fine nozzle adjustment of the airbrush revising the drawing and shading it as he went along. He worked deftly, seemingly without thinking about what he was doing because all the while he was delineating, refining, and shading on the image on the T-shirt, he was talking. He talked about how he became interested in airbrush illustrating when he was 15 years old. He started by observing.

"A couple of guys I used to watch draw- Ricky and Arab, they called themselves, they operated out of the Flea Market Mall - went over to Hawaii and, I suppose, became rich men air brushing T-shirts and Polynesian shirts for the tourists." Olsen has thought about doing the same thing, going overseas, but to Europe instead of Hawaii, and "drawing pictures of Big Ben or the Eiffel Tower for the American tourists over there; then, they could come home and show off their T-shirts to their friend to prove where they've been."

Olsen has already been around the world, and has already been in business for himself, so an extended tour abroad, for fun and profit, would be nothing new to him.

"The first business I had was a studio on Marine Avenue in Newport Beach. It was called Rembrandt Studios. I had it for five years. The funny thing is that I'd never painted a T-shirt in my life. I just opened my doors and started doing it. Always knew I could." Besides owning a business, Olsen was Art Director at KCOP-TV. After that he took a sign painting course at L.A. Trade Tech and some courses from California Institute of Arts. Consequently, he dabbles in various painting and graphics media.

"Of course, T-shirt illustrating is still my bread and butter, and I could do it a lot better than I do, but on the one hand, I am a perfectionist; and on the other, I'm too damned impatient," he said, pointing to the illustration he had just completed. He had air brushed the same picture 20 times or so before. "It's not my best effort. I get sloppier and lazier each time I recopy an image." The illustration, however, on the T-shirt bore a striking resemblance to the one on the card.

It was good enough, in fact to be hung in someone's living room. But how do you frame T-shirts?

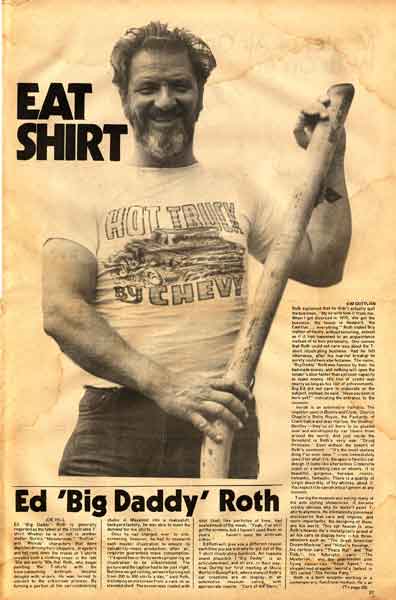

Ed Big Daddy Roth is generally regarded as the father of the illustrated T-shirt. Whether he is or not is another matter. But his "Monsterman," "Ratfink" and "Weirdo" characters that were depicted driving their choppers, dragsters and hot rods down the fronts of T-shirts created such a clothing craze in the late 50's and early '60s that Roth, who began painting the T- shirts with the time-consuming airbrush, became deluged with orders. He was forced to convert to the silkscreen process. By turning a portion of his car-customizing studio in Maywood into a makeshift backyard factory, he was able to meet the demand for his shirts.

Once he had changed over to silk-screening, however, he had to research each master illustration to ensure its sale-ability - mass production, after all, requires guaranteed mass consumption. "I'd spend two or three weeks preparing an illustration to be silkscreened. The picture and the caption had to be just right. But once we got rolling, were were turning out from 200 to 300 shirts a day," said Roth, dislodging an old screen from a rack on an elevated shelf. The screen was coated with soot, like particles of time, [that] had sealed much of the mesh. "Yeah, I've still got the screens, but I haven't used them in years ....haven't used the airbrush either."

Ed Roth will give you a different reason each time you ask him why he got out of the T-shirt illustrating business. All reasons sound plausible ("Big Daddy"' is an articulate man) , and all are, in their way, true. During our first meeting at Movie World in Buena Park, where many of Roth's car creations are on display in an automotive museum called with appropriate inanity, "Cars of the Stars."

Roth explained that he didn't actually quit the business. "My ex-wife took it from me. When I got divorced in 1970, she got the business, the house in Newport, the Cadillac...everything." Roth stated this matter-of-factly, without sniveling, almost as if it had happened to an acquaintance instead of to him personally. One senses that Roth could not care less about the T-shirt illustration business. Had he felt otherwise, after his marital breakup he surely could start anew. The name, "Big Daddy" Roth was famous by then. He had made money, and nothing will open the lender's door faster than a proven capacity to make money. His line of credit was nearly as long as his list of achievements. Big Ed did not care to elaborate on the subject; instead, he said, "Have you seen in here yet?" Indicating the entrance to the museum.

Inside is an automobile Valhalla. The roadster used in Bonnie and Clyde, Charlie Chaplin's Rolls Royce, the Pacard of Clark and Jean Harlow, the Beatle's Bentley - they're all there to be gloated over and worshipped by car lovers from around the world. And just inside the threshold is Roth's very own "Druid Princess." Even without the benefit of Roth's comment - "It's the most useless thing I've ever done." - one immediately sees it for what it is: the apex in fanciful car design. It looks like a horseless Cinderella coach or a wedding cake on wheels. It is beautiful, gorgeous, baroque, rococo, romantic, fantastic. There is a quality of virgin absurdity, of fey whimsy, about it. You expect it to vanish into a figment at any moment.

Touring the museum and seeing many of his auto styling showpieces, it became visibly obvious why he doesn't paint T-shirts anymore. He intimates by piecemeal disclosures that cars and engines and more importantly, the designing of them are his world. This car heaven is also Roth's heaven. He's nostalgically proud of all his cars on display here his three wheelers such as "The Great American Dream Machine" and "Hitler's Revenge," his cartoon cars "Peace Rat" and "Rat Fink," his futuristic cars "The Mysterion," and the pearlescent pink flying saucer-like "Road Agent," his streamlined dragster (world's fastest in '67) called "The Yellow Fang."

Roth is a born sculptor working in a contemporary, functional medium. He's an artist, not a businessman, and he admits it: "Bread is my biggest problem. I have a hard time balancing out my life between making a lot of money and having a lot of fun." And so, he had implied another reason that he doesn't bother with shirt painting: it became work instead of fun. At one time, painting pictures and caricatures on shirts had been fun for him. . . back in the old hot-rod days.

Roth recalled that T-shirt illustrating evolved rather abruptly and unexpectedly out of his car-customizing, road-dragging metier. "It was sorta an outgrowth of the car clubs that came into existence right after the war (W.W.II). The hot-rod guys used to meet in these drive-ins around town and bet each other whose rod was the fastest. They'd rap their pipes and skid their wheels and go off someplace to race a little ... they'd race for pink slips. Street racing was the favorite thing for a long time after the war; a whole generation participated in it.

"It got kinda cold racing at night, you know, so we used to go to these army surplus stores around town and pick up these aviator jackets, the brown leather type. They only cost a buck or buck and a quarter back then. Some of the guys even bought the aviator caps with the goggles and flaps coming down the sides.

For fun and sometimes profit, Roth, a teenager and a math and engineering student at East Los Angeles Junior College (he lacked a year to graduate from UCLA) in the late '40s, would do artwork for the various car clubs in town. It became the fad of car club members to wear their club's insignia and a name on the backs of their aviator jackets. Roth was deep into all aspects of the hot-rodding scene; since he was artistically inclined and because of his background in drafting and graphics, he quite naturally began doing illustrations on jacket backs.

But roadster dragging on the city streets evolved into an era of dragster racing on a track. Where formerly, car clubs surreptitiously engaged in vehicular - and sometimes, bodily - combat under cover of night, the speed contest became more of a daytime sort with a festive, rathe than odious, atmosphere. Custom car shows and hully-gully dances were frequently accompanying events at the "drags." The dernier croi of the day was for the girls, bouffant hairdos, frilly blouses and sheath like capris that clung to their gluteus maximi like the skin of a peach; and for the boys, Fabian hair styles, white levis and brightly plaided sport shirts or white T-shirts (the aviator jackets were out. They were becoming scarce; the World War II surplus was running low, and the ones manufactured by running low , and the ones manufactured by private companies were much more expensive. In any case, the heavy leathered jackets had outworn their usefulness - since Pendleton wool shirts seemed sufficient for the cool but otherwise mild California evenings.

One day, at a custom car show, Ed Roth was doing some detail work such as pin-striping on one of his cars when someone wearing a T-shirt walked up and asked him to draw a "car-toon" on it. In no time at all, Roth was back to illustrating on clothes, only this time it was on T-shirts instead of jackets. Pretty soon, he was touring the car show circuit and doing nothing except airbrushing comic and monster characters onto T-shirts, but the characters he drew were always related to the hot-rodding, car-customizing milieu.

Ed gave yet another reason why he left the T-shirt illustration business, and maybe it's the ultimate one. The day after the Movie World tour, I went down to his studio in Maywood to take some photos of him. It was Saturday and had been raining all morning. It was well past noon, but Ed had just gotten up. "I got in kinda late last night," he said, looming disheveled like a yawning giant in the doorway. Roth is a tall, hefty, goateed figure resembling a wrestler projected onto a movie screen. We went out back to his shambled work area - a nightmare of fiberglass molds, frames, engine parts and tires and wheels; the random litterings of almost 20 years of vehicle designing. Ed climbed up to a loft and grabbed about a half-dozen wrinkled, stained and illustrated T-shirts out of a black polyethylene bag - "Just happen to have a few stashed away. " He managed to squeeze his hulk into one without somehow busting the seams. A dozen camera clicks and a thousand or so words of rambling conversation later, he says: "Recreation -- that's the big thing these days. The kids don't like to work with their hands anymore. They turned from cars onto drugs. It happened in '67; that was the height of Haight-Ashbury scene up on 'Frisco. I couldn't seem to do anything for the kids after that. They weren't buying my shirts anymore because I didn't keep up with what was happening. They were buying shirts that said 'Are you man enough to eat Granny Goose' and 'Cocaine' in Coca-Cola lettering. They weren't interested in captions or slogans such as 'Fords just eat up Chevies.'" (The T shirt illustration to this caption shows a Ford with teeth for a grill and predatory eyes for headlights and the tires are shaped like mittens with a knife and fork in each. A cowering little Chevy looks up in horror at this big, ravenous Ford. Another example: The caption reads "I'm just made about my Volks" and shows a maniacal Frankenstein head leering out of the cab of a stubby VW. "I just go along my own way now," Roth said.

"Big Daddy" Roth has really always gone his own way. He's a Herculean character inside and out who pretty much defines his own image. If the image is popular, well and good; if not, that's just too bad.

Roth has a tombstone with his name on it over at Movie World. The name was chiseled out in the style of the distinctive Roth signature: the last stroke of the "R" curling like a tail under the other letters and the serif on the "T" spread out over the "O" and "H". Below the name, it says "Won a Few, Lost a Few." That's the way he wants it, and that's the way it is.

|

|

|

|